Fueling is a key part of efficient fleet operations. The same holds true when the “fuel” is electricity. For decades, fleet operators have managed vehicles powered by internal combustion engines (ICE) that run on gasoline or diesel. Refueling those vehicles is quick — it takes just minutes, adds hundreds of miles of range, and the costs depend on fuel price, not the rate at which fuel is delivered.

Charging electric vehicles (EVs) works differently. It takes a little more time, can be done while vehicles are unattended, and the cost depends on electricity rates rather than fuel prices. But just like with ICE vehicles, understanding how, where, and when you “fuel” your EVs can make a big difference in operational efficiency and cost control.

An electric vehicle connects to an external power source — typically the electric grid — through a charger, also known as electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE). The process is as simple as plugging in a cable, but there’s more flexibility in how and where charging happens — and that flexibility can affect both charging time and cost.

Fleet operators are already familiar with measuring efficiency in miles per gallon (mpg) — a simple way to gauge how far a vehicle travels on a certain amount of energy. For EVs, the same concept applies but is measured in miles per kilowatt-hour (kWh), or sometimes its inverse, kWh per mile. The energy contained in one gallon of gasoline is about 34 kWh, so it’s just a new way of thinking about the same principle: how much energy it takes to move your vehicle a mile.

In the following sections, we’ll explore the different types of charging available, how charging power and capacity affect charge times, and what to expect in terms of the cost of both charging and installing infrastructure.

In simple terms:

Energy = Power × Time

So if your charger delivers more power or has more time, your vehicle receives more energy.

A small light-duty vehicle might need about 25 kWh to drive 100 miles, while a Class 8 truck could need 250 kWh for the same distance.

Light-duty = 25 kWh per 100 miles

vs.

Heavy-duty = 250 kWh per 100 miles.

Every fleet has unique operating needs, and the right charging setup depends on how your vehicles operate and rest. Not all chargers work the same way. Electric vehicles (EVs) can be charged using alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC) — the difference comes down to where the power conversion occurs.

The electric grid delivers AC power, but an EV’s battery can only store DC power. Somewhere between the grid and the battery, the power must be converted. The equipment that performs this conversion is called an inverter and where it’s located determines the type of charging:

AC Charging

AC charging is the most common and cost-effective option for most fleets. It’s ideal when vehicles are parked for longer periods, such as overnight or during shift changes.

DC Charging

DC charging is designed for speed. Because the conversion from AC to DC occurs within the charger itself, power flows directly into the battery — allowing for much faster charging.

Which Type Does Your Fleet Need?

The type of charging your vehicles support depends largely on the vehicle itself:

Tip for fleets:

Many operators use a mix of both — AC chargers for routine, overnight charging and DC fast chargers for vehicles that need to get back on the road quickly.

Heavy-duty space — may support only DC charging.

Charging Connectors

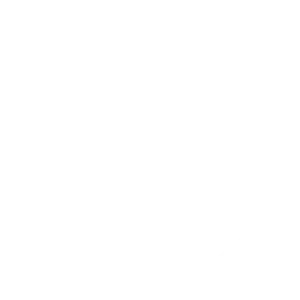

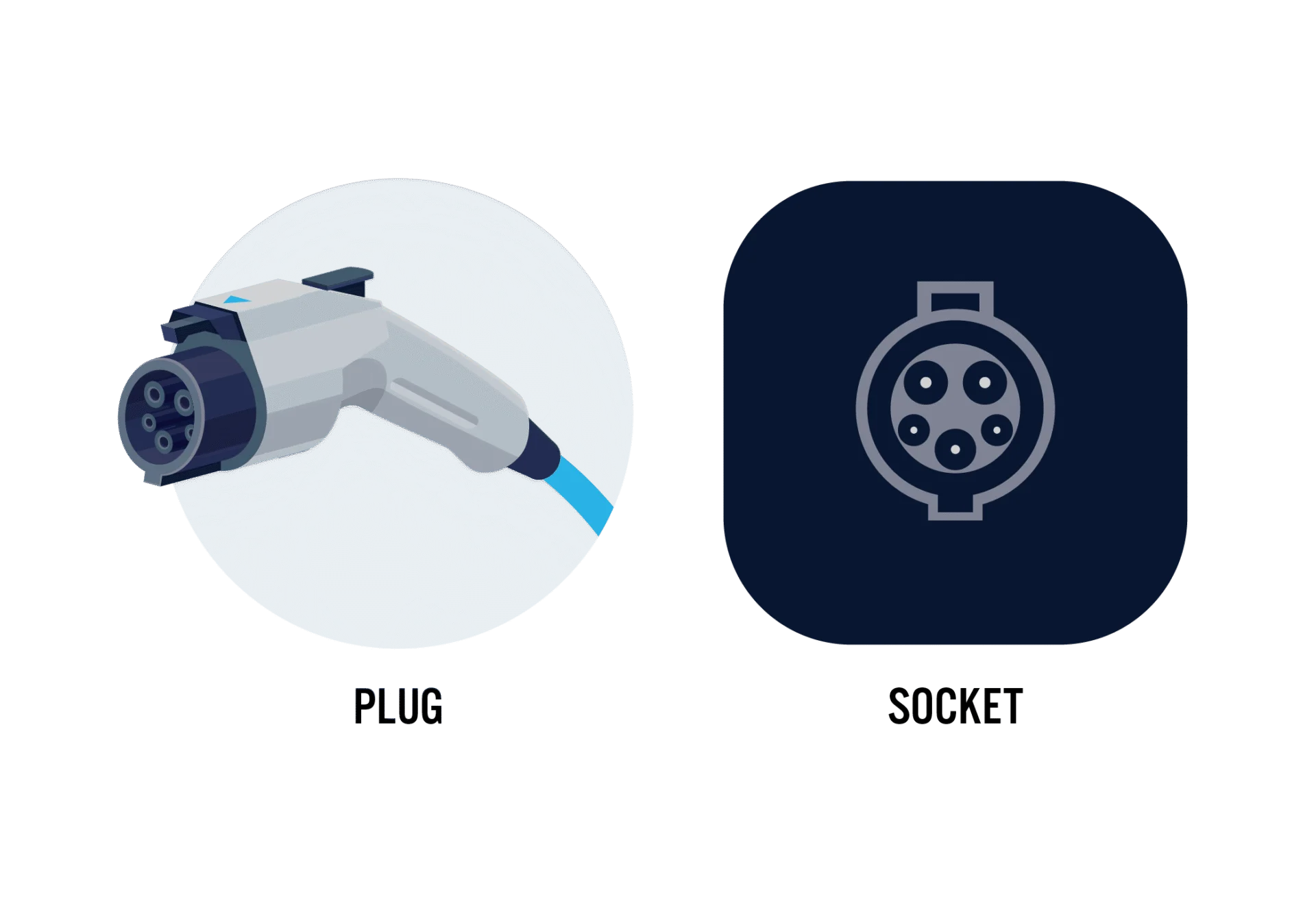

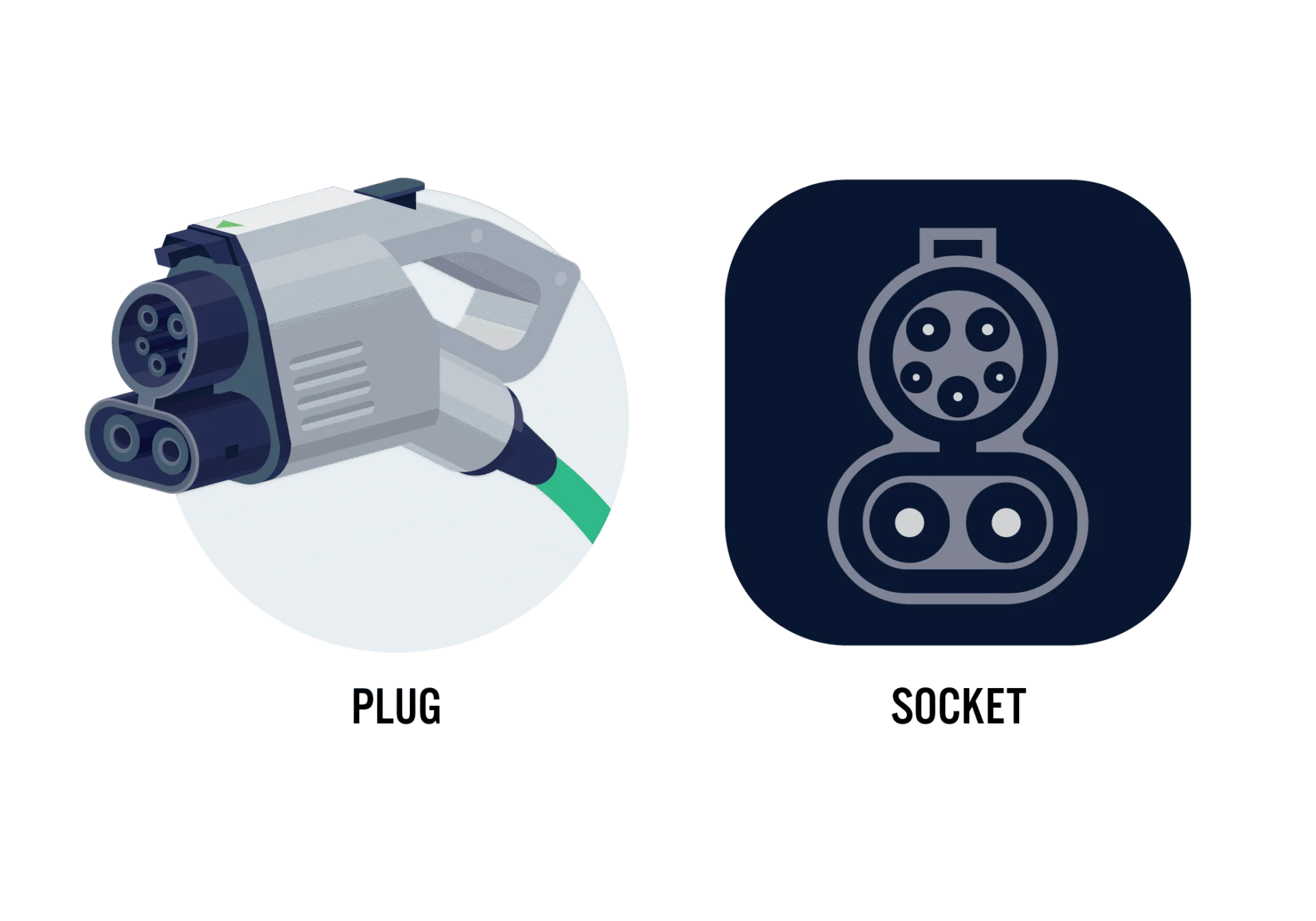

In addition to choosing between AC and DC charging, it’s important to understand the different charging couplers or connectors — the physical connectors that link a vehicle to the charger. Several standards are in use today, each designed for specific vehicle types and charging power levels. Select a charging plug below for more details:

Level 2 AC Charging (J1772): Standard plug for most passenger and light-duty vehicles in North America. It provides AC charging only, up to 19.2 kW.

SAE J1772 Combined Charging System (CCS): Common for non-Tesla vehicles, supporting by AC (up to 19.2 kW) and DC (up to 350+ kW).

SAE J3400 North American Charging System (NACS / J3400): A standardized version of Tesla’s proprietary connector, now adopted by most automakers for their light-duty vehicles; supports AC up to 22.2 kW and DC up to 350+ kW.

J3271 Megawatt Charging System (MCS / J3271): High-power DC charging that supports 1,000+kW or 1+ megawatt (MW).

CHAdeMO: The CHAdeMO connector was one of the first fast-charging standards used mainly by early Japanese EVs. It’s now being phased out in North America as newer connector types become the industry standard.

Charging Solutions for Fleet Operators

Unlike fueling stations, EV chargers can be placed almost anywhere with access to power and parking — even on your own property.

For smaller fleets, on-site charging offers convenience and cost control. Others may rely on public or contracted charging networks.

When deciding between owning chargers or using public options, consider:

Some regions also offer Charging-as-a-Service (CaaS) — where you pay per kWh and a third party owns and maintains the chargers.

Charging time isn’t one-size-fits-all — it depends on how much energy your vehicles need and how quickly that energy can be delivered. A few key factors determine how long a full charge will take:

In simple terms, charging time depends on how far your vehicle needs to go and the power level of the charger being used.

For example, a light-duty delivery van charging overnight with an AC Level 2 charger might take several hours to recharge, while a fast DC charger could add similar range in under an hour.

Tip for fleets: Knowing your vehicles’ dwell times and daily driving distances can help you select chargers that balance cost and convenience.

Tip for fleets:

Knowing your vehicles’ dwell times and daily driving distances can help you select chargers that balance cost and convenience.

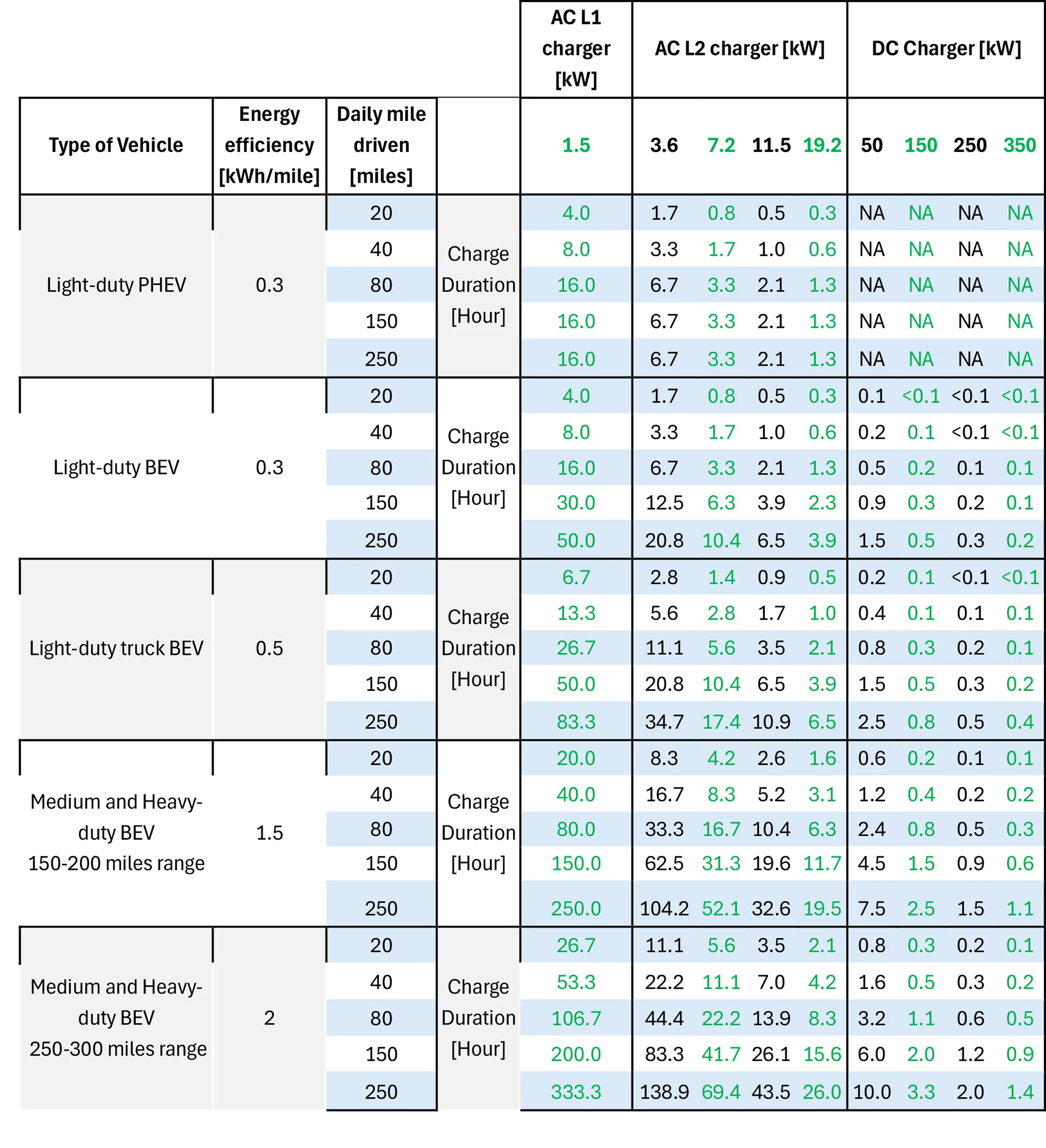

Charging time can be estimated based on how many miles of driving the charging must support and the power level of charging being used. Click here for more information: The following table, calculated as noted below, estimates the time required for charging, depending on the charger power, the type of vehicle, and the daily miles driven.

The charging duration (in hours) is determined using the charger’s power rating (in kW), the vehicle’s daily mileage, and its efficiency (in kWh/mile):

Charge duration [h] =

(miles driven [miles] × vehicle efficiency [kWh/mile]) ÷

(Charger power [kW] )

For instance, if a 100 kW charger is used to charge a MDHD BEV, such as an electric bus, driving 150 miles a day with an efficiency of 2kWh/miles, then:

Charge duration [h] =

(150 [miles] × 2 [kWh/mile]) ÷ (100 [kW] )=3 h

For a PHEV, where electric driving is limited (40 miles is typical), it was assumed that these vehicles do not support use of DC charging:

Electricity costs are typically more stable than gasoline or diesel prices, but they can also be more complex. Unlike fuel costs, which are determined by price per gallon, EV charging costs depend on how and when electricity is used.

Because fleets vary widely in size, vehicle type, and operations, determining a simple “cost per mile” figure can be challenging. However, a few key factors consistently shape the total cost of charging:

Because of these variables, it’s helpful to work with your electric utility to understand your available rate options and how they affect your fleet’s bottom line.

To make this process easier, many utilities and clean transportation organizations offer EV cost calculators and fleet advisory services that estimate charging expenses and potential savings.

Helpful Resources:

Tip for fleets:

Your utility’s fleet team can often help you analyze your charging patterns and choose the best rate structure to minimize both monthly costs and demand charges.

Unlike internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, EVs can charge safely for long periods without supervision. As long as the charging duration fits within a vehicle’s dwell time — the period when it’s parked and not in use — longer sessions aren’t an issue.

For example, if a truck is parked overnight for 10 hours, charging can last that entire time without affecting operations. Faster charging is possible, but it requires higher-power equipment, which increases both infrastructure and interconnection costs. In most cases, it’s a balance between charging speed, operational flexibility, and cost.

Tip for fleets:

Coordinate with your utility to find a rate plan that supports your charging schedule and minimizes both capital (CAPEX) and operating (OPEX) costs.

How Utility Rates Influence Charging Strategy

Your utility’s rate structure can have a big impact on how and when it’s most cost-effective to charge your fleet:

Longer charging sessions are perfectly acceptable when they align with your vehicles’ schedules. The key is to match charger power, vehicle dwell time, and utility rate structure to create a cost-effective, reliable charging strategy.

For many fleet operators, one of the first big decisions in electrification is whether to rely on public charging networks or install charging equipment on site. Building your own charging infrastructure provides greater control and convenience, but it also comes with upfront costs for equipment, installation, and future maintenance.

Before making a decision, take these two important steps:

eTRUC report:

EPRI’s Electric Truck Research and Utilization Center (eTRUC), California’s premier research hub for electric technologies in truck applications, published a report that includes cost calculations for several example sites.

Tip for fleets:

Start planning early with your utility and site electrician. Coordinated design and permitting can prevent costly rework and keep your electrification project on schedule.

The Electric Vehicle Infrastructure – Locally Optimized Charging Assessment Tool and Estimator (EVI-LOCATE) is a comprehensive design tool that helps you create an electric vehicle (EV) charging station deployment plan, from layout to cost estimates.

This case study walks through how to use EVI-LOCATE:

Level 2 Charger Use Case